June 2002, Issue No. 194

A monthly report on environmental

and pesticide related issues

In This Issue

Defusing

Diffuse Knapweed: Biological Control of an Explosive Weed

FEQL

Advisory Board Meets

Upcoming

Conferences/Announcements

NOTE

ABOUT PRINTING A HARD COPY

Some AENews feature articles are available

in Portable Document Format (PDF) version, which is recommended for

printing. If you do not have Adobe

Acrobat Reader (required to read PDF files), this free program is

available for download at http://www.adobe.com/prodindex/acrobat/readstep.html

If you choose to print from the HTML version you currently see on

your screen, you may need to set your browser's printing preferences

so that no margins are cropped.

|

|||

| Defusing Diffuse Knapweed: Biological Control of an Explosive Weed | |||

| FEQL Advisory Board Meets | |||

| Upcoming Conferences/Announcements | |||

NOTE

ABOUT PRINTING A HARD COPY

Some AENews feature articles are available

in Portable Document Format (PDF) version, which is recommended for

printing. If you do not have Adobe

Acrobat Reader (required to read PDF files), this free program is

available for download at http://www.adobe.com/prodindex/acrobat/readstep.html

If you choose to print from the HTML version you currently see on

your screen, you may need to set your browser's printing preferences

so that no margins are cropped.

Return to Agrichemical and Environmental

News Index

Return to PICOL (Pesticide Information Center On-Line) Home Page

Pesticide Exposure MonitoringBackground and Perspectives on Mandatory Cholinesterase Testing |

Click here for PDF version of this document (recommended for printing). Should you not have Adobe Acrobat Reader (required to read PDF files), this free program is available for download at http://www.adobe.com/prodindex/acrobat/readstep.html |

Marcy J. Harrington, Communications Coordinator, PNASH

The Washington State Supreme Court has ordered the Washington Department of Labor and Industries (L&I) to develop a rule for mandatory testing of agricultural workers who handle high-toxicity organophosphate (OP) or carbamate insecticides. The goal is to identify workers who are at increased risk for overexposure and subsequent poisoning.

Legal Background

Cholinesterase is an enzyme that can be measured in the human body. Its level can be used as an indication of possible over-exposure to certain toxins including OP and carbamate pesticides. In 1995, a Technical Advisory Group (TAG) formed by L&I found that cholinesterase monitoring was technically feasible and necessary to protect worker health. TAG recommended further review toward implementing a mandatory cholinesterase-monitoring program.

A recent court case brought this issue back into the spotlight. A lawsuit was filed against the Washington Department of Labor and Industries on behalf of Juan Rios, Juan Farias, and all agricultural pesticide handlers and farm workers who mix, load, and apply pesticides. In February 2002, the state Supreme Court found that L&I had violated the Washington Industrial Safety and Health Act of 1973 (WISHA) by denying the farm workers' request for rulemaking on a mandatory cholinesterase monitoring system.

This ruling set a precedent, according to Dan Ford of Columbia Legal Services, counsel for the farm workers in the case. Now Washington L&I has a statutory duty to initiate rulemaking when requested and when L&I's record shows that the requested rule is both necessary and doable.

What Happens Next?

Washington's monitoring system will require agricultural employers to conduct blood tests of workers who are at risk for OP and carbamate poisoning. The specific requirements, however, are left to L&I's discretion. WISHA requires that L&I provide the "most adequate" protection that is feasible to protect workers against material impairment of health.

Over the next several months, L&I will initiate rulemaking in a process that allows for broad stakeholder input to include labor advocacy groups, grower representatives, governmental agencies, and technical experts. In order to give stakeholders the best opportunity for involvement, public stakeholder meetings will be scheduled throughout the state and at times that fit around the agricultural industry's busy seasons. The development of the new cholinesterase monitoring rule will use the WISHA 1993 voluntary cholinesterase monitoring guideline (WAC 296-307-14520) as a template. Although a specific timeline for adoption of a final rule has not been set, the preliminary goal is to have a rule in place by February 15, 2003.

A Look at Cholinesterase

Cholinesterase, or more properly acetylcholinesterase, is an enzyme essential for normal functioning of the nervous system. In the body, acetylcholinesterase inactivates the chemical messenger acetylcholine, which is normally active at the junctions between nerves and muscles, between many nerves and glands, and at the synapses between certain nerves in the central nervous system.

When cholinesterase levels are low because of excessive inhibition, the nervous system can malfunction, producing pesticide-poisoning symptoms such as fatigue, lightheadedness, nausea, vomiting, headaches, and seizures. If levels get low enough, subsequent exposure to OP or carbamate insecticides can result in death.

A basic monitoring system would periodically test cholinesterase levels in the blood of those people at risk for cumulative exposure and insecticide poisoning. Blood samples can be drawn at a clinic and sent to a laboratory for evaluation or the entire procedure can be performed at the worksite with field test kits. Workers shown to have dangerous levels of inhibition are then identified and reassigned to prevent further exposures until their depressed cholinesterase level rises close to the normal level.

The recommendations outlined in the TAG report Cholinesterase Monitoring in Washington State were used by the Washington State Supreme Court to decide if a monitoring system was feasible. The report recommended:

- Medical supervision for workers who mix, load, or handle Class I or II OPs or carbamates.

- Testing for workers who handle pesticides more than 3 consecutive days, or more than a total of 6 days in a 30-day period.

- A single pre-exposure baseline measurement taken from workers each year prior to exposure.

- Follow-up testing every three to four weeks (depending on spray cycle) until spray activities are completed for the season.

- Removal of workers whose red blood cell cholinesterase is at or below 70% of baseline levels or plasma cholinesterase is at or below 60% of baseline. Workers would not be exposed to OP or carbamate pesticides until their cholinesterase levels return to 80% or more of their baseline.

Lessons from California, Concerns in Washington

Around the nation, many employers have voluntarily adopted cholinesterase monitoring as a precaution for their workers, but California is the only state with a mandatory cholinesterase monitoring standard. They have required cholinesterase monitoring since 1974 for all workers with more than six days’ exposure in a single month to Class I and II OPs or carbamates. (Certain exceptions apply, such as those individuals working with closed application systems.) California employers have reduced exposures and the need for worker testing by spreading out application duties among several trained workers.

According to Dr. Mike O'Malley, Director of Employee Health at the University of California at Davis and a medical consultant with Cal/EPA, California has seen the benefit of protecting people from cumulative exposure and the possibility of poisoning. He also pointed out that the system provides an opportunity for educating employees about pesticide risks and personal protection.

Here in Washington, there are lessons to be learned and concerns to be addressed. Mary Miller, a coordinator of the TAG, suggests that "a reliable system could be developed by working with the medical, laboratory, and agricultural community. Such a system for testing, interpreting and feedback of results would be a model for surveillance of agricultural worker's health."

By addressing the following issues, our state can conduct a reliable cholinesterase monitoring program.

Impact on Employers. Currently, the Washington Growers League is conducting a survey of all growers who may be impacted by the new ruling (those who use Class I and II OP and carbamate insecticides). The Growers League will work with L&I to ensure that affected employers have an opportunity to be fully involved in and informed of the rulemaking. Mike Gempler, Executive Director of the Washington Growers League, said employers want a system with maximum effectiveness and relevance for the applicators tested, a good cost/benefit analysis, scientific integrity of the testing (both in the field and in the lab), and employer and employee education.

Scientific Integrity. Scientists have put considerable thought into how to structure a good cholinesterase monitoring system. The challenge is to design a system that prevents false negative and false positive readings. The elements of an effective method should include:

- Medical Supervision. Dr. John Furman, Occupational Nurse Consultant, WISHA Policy and Technical Services, supports the recommendations of the TAG report that "medical supervision is recommended for agricultural workers who handle Class I or II organophosphate or carbamate pesticides. A medical supervisor may include either a licensed physician or advanced registered nurse practitioner. Primary responsibilities of the medical supervisor may include: providing and interpreting baseline and serial cholinesterase laboratory tests; providing feedback of significant results to the employer, employee, and regulatory agencies as appropriate; recommending employee removal from pesticide exposure or review of work practices; and, maintaining copies of the cholinesterase monitoring results and other related employee medical records."

- Uniform Testing. Dr. O'Malley of UC Davis said California only recently standardized its laboratory testing and suggested Washington standardize from the beginning. Standardization allows a test in one lab to be followed-up in another. This is especially important in agriculture, where workers frequently change employers. Selection of this uniform method will not be easy. Dr. Barry Wilson at UC Davis explained that there is no agreed-upon standard method for testing and scientists will need to use an accurate monitoring assay.

- Centralized Laboratory Monitoring. Dr. Matthew Keifer with the University of Washington's Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center (PNASH) suggested that a centralized authority monitor laboratories to ensure the validity and reliability of their testing.

- Centralized Data Maintenance. The data collected during testing should be maintained in a central repository charged with following trends in pesticide exposure levels. In this way, the information can be used to benefit public health, Dr. Keifer said.

- Proper Sample Treatment. The blood samples must be delivered to the laboratory with procedural care including refrigeration.

- Accurate Carbamate Test. Dr. Keifer stated that currently there are no accurate testing methods for carbamate insecticides. In this case, cholinesterase inhibition reverses quickly, so the inhibition level seen by the time it reaches the laboratory is not what was found in the body of the worker.

- Quick

Results. The cornerstone of this system’s effectiveness

is the removal of farm workers from exposure when depressed levels of

cholinesterase are found. If test results are not returned quickly,

workers may not be removed in time to prevent another exposure.

Education. Several groups will require specialized training. Agricultural employers will need to be fully informed about the compliance standard and the principles supporting it. Workers who handle pesticides will need to understand the monitoring system, how it will protect their privacy, and what they can do to minimize their exposure to pesticides. Health care providers at clinics, hospitals, and laboratories must understand and comply with the procedures necessary to ensure the reliability and coordination of the testing and monitoring processes.

Continued

Program Evaluation. Within the next year, we will learn how

broadly the rule will be defined. Further study is needed to understand

how widespread Class I and II OP and carbamate use is in the state and

what the incidence rate is for severe cholinesterase inhibition.

Recent federal regulations restricting the use of some OP pesticides,

such as Guthion, may have reduced the use of high-hazard pesticides. Other

mitigating factors such as "closed" pesticide handling systems

and new, safer pesticides may further reduce workers' exposure to harmful

pesticides.

The proposed monitoring system, coupled with continued data analysis,

will help document the severity of the problem. It may, over time, demonstrate

that there is no further risk to farm workers. Such information could

make routine cholinesterase monitoring unnecessary.

Where Do We Go from Here?

Many questions remain unanswered about mandatory cholinesterase monitoring in Washington. Some of the solutions will be revealed through science and others through public participation in the rulemaking. Keep your eye on AENews for follow-up articles as more information is known about the specific provisions of the new rule.

To guarantee that Washington's cholinesterase monitoring system protects workers, all affected stakeholders (workers, growers, public health professionals, and L&I staff and scientists) need to be involved in developing the rule. Full participation can ensure that the rulemaking has integrity and that the resulting system is sound.

If you would like to be involved in the formulation of the proposed rule, contact Cindy Ireland, Project Manager, L&I, WISHA Services Division at (360) 902-5522. Other good resources for your questions include the Washington Growers League at (509) 575-6315 and the Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center at 1-800-330-0827.

This article was written by the staff of the Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center, a research center housed within the University of Washington's School of Public Health and Community Medicine. For additional information you may refer to the PNASH Web site at http://depts.washington.edu/pnash or contact the author, Marcy Harrington at marcyw@u.washington.edu or (206) 685-8962.

Useful Publications

"Cholinesterase Monitoring in Washington State: Report from the Technical Advisory Group" can be obtained by contacting John Furman at furk235@lni.wa.gov (360-902-5666) or Janet Kurina at kuri235@lni.wa.gov (360-902-55478).

"Cholinesterase Monitoring: The Basics," is available by contacting Marcy Harrington at marcyw@u.washington.edu (206-685-8962).

"Guidelines for Physicians" and "Medical Supervision for Physicians" are offered by California's Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. These documents can be downloaded in pdf format at http://www.oehha.ca.gov/pesticides/programs/Helpdocs1.html.

"Jorge's New Job: Getting Tested for Cholinesterase" is worker training photo-novella in English and Spanish produced by the University of California Statewide Integrated Pest Management Project. Copies can be ordered by calling 1-800-994-889.

The Supreme Court of the State of Washington's opinion on Juan Rios and Juan Farias v. Washington Department of Labor and Industries can be found at http://www.legalwa.org.

Return to Table of Contents for the June 2002 issue

Return to Agrichemical and Environmental News Index

Return to PICOL (Pesticide Information Center On-Line) Home Page

It's Not Nice to Ignore the Queen |

Click here for PDF version of this document (recommended for printing). Should you not have Adobe Acrobat Reader (required to read PDF files), this free program is available for download at http://www.adobe.com/prodindex/acrobat/readstep.html |

Jane M. Thomas, Pesticide Notification Network Coordinator, WSU

I

was astounded, simply astounded, to discover that I, the Queen Bee of

Labels (that’s QBL to you), am being ignored. While I am sure my

Loyal Followers are not ignoring me, I have discovered that this is not

the case in some circles. No one likes to be ignored, but the QBL finds

it Royally Repugnant. It is bad enough that the U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency (that’s EPA to you) has been dragging their feet, neither

appointing nor anointing me to my Rightful Regal place as Queen Bee of

Labels (see

“If I Were the Queen of Labels,” AENews May 2000, Issue

No. 169). This alone has

stretched my normally expansive patience. Recently, however, it has come

to light that EPA is once again ignoring the QBL and that others are now

following their lead. Merciful Monarch that I am, I can forgive innocent

ignorance. What I cannot abide is willful ignore-ance. The queenly ire

might not have been so acute had all these recent incidents not occurred

in such close succession (that's succession NOT, heaven forbid, secession).

I

was astounded, simply astounded, to discover that I, the Queen Bee of

Labels (that’s QBL to you), am being ignored. While I am sure my

Loyal Followers are not ignoring me, I have discovered that this is not

the case in some circles. No one likes to be ignored, but the QBL finds

it Royally Repugnant. It is bad enough that the U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency (that’s EPA to you) has been dragging their feet, neither

appointing nor anointing me to my Rightful Regal place as Queen Bee of

Labels (see

“If I Were the Queen of Labels,” AENews May 2000, Issue

No. 169). This alone has

stretched my normally expansive patience. Recently, however, it has come

to light that EPA is once again ignoring the QBL and that others are now

following their lead. Merciful Monarch that I am, I can forgive innocent

ignorance. What I cannot abide is willful ignore-ance. The queenly ire

might not have been so acute had all these recent incidents not occurred

in such close succession (that's succession NOT, heaven forbid, secession).

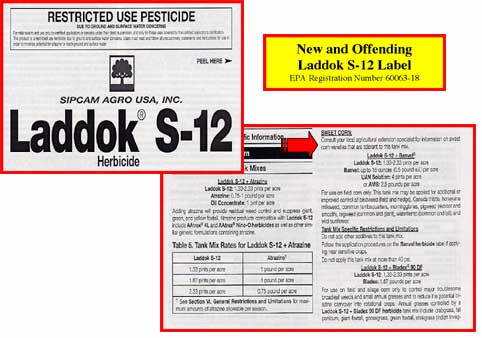

The first and second offenses were committed by Sipcam Agro. Loyal Royal Readers will recall that this company was the focus of some discussion in December 2000, Issue No. 176 of this fine publication in my article “The QBL Gets Graphic.” Sipcam Agro received quite a dressing down and was the first nominee in the new Litigious Layout Non-Anom category. You might recall that the good and true staff of Washington State University's Pesticide Information Center (PIC), took it upon themselves to present a suggestion for how this label could have been laid out that would have alleviated the problems presented by Sipcam Agro's layout. (And, not to flog a flagging horse, but the proposed layout was darn good.)

Earlier this spring, while regally rummaging through some registration materials, I was fascinated to see that Sipcam Agro was adding a new registration in 2002 for another product, also called Laddok S-12, this time designated by EPA Registration Number 60063-18. (The label discussed in the December 2000 issue of the AENews, also Laddok S-12, carries EPA Registration Number 7969-100-60063.) I was delighted with this turn of events, sure that Sipcam Agro, so embarrassed by the faux pas of their old label had decided to scrap the whole thing and register a new product altogether. I quickly flipped to the tank mix portion of the label, aglow with expectant gratification, ready to be so pleased that my gentle advice, so generously given, was appreciated and acted upon. Imagine the scene when I opened the label and found that the tank mix text was laid out EXACTLY as it had been in the Old and Offending Laddok S-12 label. By virtue of good breeding and determined dignity, I was able to stifle the scream that arose within. Barely.

Luckily the more recent pesticide registration materials often include e-mail addresses for the registrant's appropriate contact person. In this case the Registration Manager was listed as one Jon M. Gehring. After a short "time-out" to compose myself, I penned this restrained note:

My Dear Mr. Gehring,

I was very interested to see that Sipcam Agro was registering a new Laddok S-12 label in Washington since I had had such a good time making fun of the layout of the old label. (See “The QBL Gets Graphic” in the December issue of the Agrichemical and Environmental News: http://www.aenews.wsu.edu/Dec00AENews/Dec00AENews.htm#anchor1302304.) Imagine how regally disheartened I was to see that the layout of this new label is just as lousy as the layout of the old label. You have not been attentive to the Word on High from HRH The Queen Bee of Pesticide Labels (QBL to you) and the QBL is royally disappointed. Please explain yourself! I can only imagine that you received some unfortunate legal council that convinced you Sipcam Agro would be liable for Royalties had you done the right thing and used our suggested (corrected) layout. I hope that you have now realized the error of your ways.Reigning from afar,

The QBL

This missive was sent March 12 and there is, as yet, no reply on the horizon. As you can see, Sipcam Agro has done the unthinkable and has ignored the QBL not only once but twice. I believe that this puts Sipcam Agro at the top of the QBL's Wildly Wayward Registrants list. Congratulations. (I had for a brief moment contemplated calling this the Really Rasty Registrants list but upon reflection determined that this was, sadly, beneath me.)

The second ignore-ant offender to which I would draw your attention is none other than Whitmire Micro-Gen. The label in question is Durashield CS. The PIC office received a revised copy of this label late in 2001 forwarded to us from the Washington State Department of Agriculture. The label copy from Whitmire Micro-Gen included copies of what appears to be both the container label and the full label containing all of the use directions. Both carry the notation "rev. 1/01." The odd thing about this label, noticed by the PIC's ever-sharp Database Coordinator Charlee Parker, is that the full printed label is marked as a Restricted Use Pesticide while the copies of the container label carry no such marking.

I took it upon myself to call Whitmire Micro-Gen's registration folks and ended up speaking to a Darla Becker. Her response to the QBL was really rather interesting. First she was sure that I was in error even after I explained that I was looking at label copies that Whitmire Micro-Gen had submitted to the state of Washington for registration purposes late in 2001. Next she was sure I must be looking at an out-of-date label; my response was the same. Next she was sure that there really wasn't a problem because the product was a Restricted Use Pesticide and the container labels, she was sure, did carry the RUP statement. For the fourth and final time I explained what it was that I was holding in my hand and why I was concerned. Ms Becker assured me that she was sure there wasn't a problem with the Durashield CS labeling. Oddly, I was not reassured.

My next step was to try and find an on-line copy of this label. I finally found an old (rev. 1998) copy on a Whitmire Micro-Gen Web page using the Google search engine. (Don't be surprised; in this day and age even royalty are learning to make use of the modern conveniences.) This 1998 label copy was not marked as an RUP.

Finally, I conducted a survey of the information provided by Kelly Registrations for their contract states. I found that in every case, including a host of 2002 registrations, Kelly lists Durashield CS as a general use pesticide (except in Vermont where it carries a state restricted use notation).

So what, exactly, was I holding in my Queenly Hands? Was it a label with a split personality? Is it possible that Durashield CS really isn't an RUP? I don't think so. How could Whitmire Micro-Gen produce two versions of the label in the same month, marking one as an RUP and the other not, and then be so clueless as to distribute them to a state regulatory agency? Further, when Called from on High, how could a representative of Whitmire Micro-Gen (or anyone, for that matter) blow off the QBL with such assure-ance?

Finally, I would like to discuss the most recent, most flagrant ignore-ance of all. I have recently received Royal Intelligence that a mere serf at EPA, someone by the name of Jim Jones (who has the effrontery to refer to himself as the King of Labels—humff!) has developed a pilot program that enables select individuals to submit questions and comments on pesticide labels. This Web-based program allows a user to submit comments or questions about a label. By typing in the EPA number of the product in question, an e-mail is automatically (through the magic of technology) directed to the EPA product manager responsible for that item. Everyone involved in the program receives a copy of the e-mail message and EPA’s response. Mr. Jones believes that within a few months this program, now limited to five states, will expand to all 50 states. As designed this program is limited to input and participation from state's departments of agriculture and EPA regional offices.

Let the public record show that I am permanently (but luckily not fatally) offended. This could be a great idea. But where is the part where the EPA's Mr. Jones picks up the phone and consults with the QBL? Had he, I would have offered the following Royal Recommendations:

- Post all correspondence for each label so that when a person types in an EPA number one can view all preceding correspondence to see if your question/comment has already been addressed.

- Use not only the EPA number but also the product name. Consider for a moment Monsanto and EPA registration number 524-343: one EPA number, five different products.

- Use label revision information when designating the label in question so that everyone knows exactly which label copy is being discussed.

- Include distributor labels in this program. Because EPA does not review these labels I suspect that they will not be included; yet, these labels are subject to the same errors, omissions, and faults as other labels.

- Open the process to all comers. What group of people is most likely to read pesticide labels? (These pages make it obvious that it isn't EPA.) Obviously the biggest group perusing pesticide labels is pesticide users. Surely they should have easy access to this program. If EPA doesn't want to deal with the lowly public then perhaps they could agree to let the questions be filtered through Cooperative Extension. In Washington State, this is a common path for label questions.

- Summarize information annually. EPA should give an award for the label with the most problems. It would be very useful to track the most common type of problem found on pesticide labels. To this end perhaps in responding to the original e-mail the product manager could code the reply as to the type of issue that was addressed: layout, typo, usage site terminology, revision information, etc. Feeding this type of information back to the registrants and EPA might eventually lead to across the board label improvements.

Note that these are just some off-the-top-of-my-crown thoughts on this subject. Had I been involved in the planning and really given this some serious thought just imagine how good a program it might have been. I suppose that this is the price that EPA must pay for ignoring the QBL.

Take note, all you registrants out there: EPA may be ignoring me, but don't you dare or you will soon be keeping Sipcam Agro and Whitmire Micro-Gen company on the Wildly Wayward Registrants list.

In an ongoing effort to force a job offer from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Her Royal Highness The Queen Bee of Labels (HRH QBL, a.k.a. WSU's Jane M. Thomas) takes time out of her busy Royal Schedule periodically to point out oddities and aggravations on pesticide labels. It is the QBL's Opinion Most High that if she were in charge of all things label, a few RULES, combined with swift and thorough consequences for transgressors, would whip the whole pesticide label business into shape in a matter of weeks. Until such time as EPA sees the light and appoints HRH QBL to her rightful position, The Queen shall content herself with commentary such as appears periodically in these pages. HRH QBL can be reached at (509) 372-7493 or jmthomas@tricity.wsu.edu.)

Return to Table of Contents for the June 2002 issue

Return to Agrichemical and Environmental News Index

Return to PICOL (Pesticide Information Center On-Line) Home Page

Natural EnemiesA New Weapon in the War on Hop Pests |

Click here for PDF version of this document (recommended for printing). Should you not have Adobe Acrobat Reader (required to read PDF files), this free program is available for download at http://www.adobe.com/prodindex/acrobat/readstep.html |

Dr. David G. James, Entomologist, WSU

The

War So Far

The

War So Far

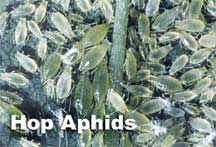

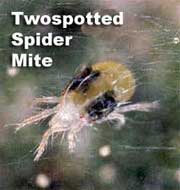

Hops are attacked by several insect and mite pests, the most important being the hop aphid (HA) and the twospotted spider mite (TSSM). Insecticides and miticides are routinely used to control these pests on hops grown in Washington. However, insect and mite management in Washington hops is currently being re-evaluated due to increasing concerns over the cost-effectiveness, reliability, and sustainability of chemical control. Chemical control of mites in hops is often difficult due to the large canopy of the crop and problems with miticide resistance (James and Price 2000).

Natural

Weapons

Natural

Weapons

Research to date on the biological control of mites in hops has centered on using predatory mites, either introducing additional mites to the hop yard or conserving those present (Campbell and Lilley 1999;Pruszynski and Cone 1972). Efforts have not shown much commercial promise. While predatory mites are undoubtedly important agents against TSSM in hops, support from other mite predators appears to be necessary to provide levels of biological control acceptable to growers.

The Army Concept

The use of ‘armies’ of different predators and parasitoids in crop ecosystems, as opposed to single specialist type biological control agents, is receiving considerable interest as a crop protection strategy in a number of crops (Ehler 1992; Murdoch, Chesson and Chesson 1985; Riechert and Lawrence 1997). Control using the entire complex of natural enemies that prey upon a pest is often highly effective and very sustainable.

An

Army is Available

An

Army is Available

To determine the importance and potential of the local natural enemy community in regulating populations of TSSM and HA on hops in Washington, we monitored the monthly abundance of pests and predators on commercial (pesticide-treated) and escaped (pesticide-free) hops during 1999 and 2000. The mean abundance of TSSM and HA in both years when analyzed over the season was low and did not differ significantly between commercial and escaped hops (James, Price, Wright and Perez 2001). Numbers of mites at escaped hop sites did not exceed five per leaf in any month. Thus, damaging mite populations did not occur even when sprays were not applied. The mean abundance of predatory mites in both years also did not differ significantly between commercial and escaped hops. However, the abundance of other predators of mites (e.g., mite-eating ladybeetles, minute pirate bugs, predatory thrips) was more than three times greater on escaped hops than in commercial hop yards, suggesting that this component of the natural enemy fauna was highly important in TSSM biocontrol.

Gathering

Intelligence

Gathering

Intelligence

I decided to take a closer look at pest-natural enemy relationships and dynamics in hops by designating a 2.7-acre hop yard at WSU-Prosser as the “Biological Control Yard.” No insecticides or miticides were used and populations of TSSM, HA, and natural enemies were monitored intensively throughout the season in 2000 and 2001. In 2000, TSSM and HA were first seen on May 3 but remained at low levels for the next two months (Figure 1). TSSM did not exceed one per leaf until July, although ‘hot spots’ were observed in the yard during June. These consisted of single bines (i.e., “hop vines”) where mite populations sometimes exceeded ten per leaf (the level at which hop growers usually decide to spray). However, in all instances significant populations of mite-eating ladybeetles and minute pirate bugs were also present, effectively preventing the ‘hot spots’ from spreading. Predatory mites did not occur in large numbers until July when they contributed in a major way to suppressing TSSM. Numbers of TSSM peaked at six per leaf in mid July (far below the economic damage threshold) and remained below five per leaf for the rest of the season. No significant mite damage was found in harvested cones.

HA populations increased to about twelve per leaf in late June before declining rapidly in early July to one or two per leaf. Numbers increased to five per leaf in September. Hop growers generally only spray for HA when they exceed fifteen or twenty per leaf. Predators, particularly native ladybeetles, big-eyed bugs, and minute pirate bugs, appeared to be largely responsible for the low numbers of HA.

In 2001, overwintered TSSM were first seen on sprouting hops in late March along with predatory mites, which controlled the spider mites by mid-April when hop plants were burned back to synchronize growth for training on strings. No TSSM were seen on new growth until late June when small numbers occurred in hot spots, along with mite-eating ladybeetles and minute pirate bugs (Figure 2). These predators and others (predatory midges, predatory thrips) maintained TSSM at low levels throughout July. Predatory mites were generally absent until late July. In late July and early August TSSM increased to about seven per leaf and then to eighteen to fifty-three per leaf for two or three weeks. Predatory mite populations also increased rapidly (up to fourteen per leaf), bringing TSSM under control by the end of the month. No economic damage to hop cones was caused by the late season spider mite population increase. Hop aphids appeared in mid-May but stayed at less than one per leaf until late June when they increased, reaching seventeen per leaf by mid-July and twenty-five per leaf by the end of the month. Numbers fell dramatically in early August to less than four per leaf, mainly due to invasion by the multicolored Asian ladybeetle, which was introduced into the United States many years ago but has only recently reached south-central Washington.

FIGURE 1 |

FIGURE 2 |

|

|

|

|

| Abundance of selected pests (TSSM, HA) and beneficials (minute pirate bugs, mite-eating ladybeetles) in the Biological Control Hop Yard at WSU-Prosser in 2000. | Abundance of selected pests (TSSM, HA) and beneficials (mite-eating ladybeetles, minute pirate bugs) in the Biological Control Hop Yard at WSU-Prosser in 2001. |

Complex Arsenal Key to Defeat

Our results indicate that biological control provided by an assemblage of natural enemies has the potential to provide effective management of mites and aphids on hops. The more biological ‘weapons’ we employ, each with their own slightly different mode of action in preying on the target pests, the more comprehensive our warfare will be. Relying on a single natural enemy, like predatory mites, restricts control efforts and reduces the prospects of success and sustainability. The key to successful biological control of mites in hops appears to be effective regulation of hot spots during spring. Uncontrolled expansion of hot spots leads to high densities of TSSM throughout hop yards. Mite-eating ladybeetles, minute pirate bugs, and other predators can, together, ensure that mite populations remain below damaging levels.

New Weapons, Old Weapons

The challenge for the future is to integrate community-based biological control of mites and aphids into commercial hop production with its chemical inputs. A program has been established at WSU-Prosser that will determine the compatibility of all currently used hop chemicals with biological control (James 2001). In the course of this program, we have developed toxicity profiles for most hop insecticides with respect to beneficials including predatory mites, mite-eating ladybeetles, and multicolored Asian ladybeetles. It is clear that some currently used materials like abamectin and imidacloprid must be replaced by softer alternatives if conservation biological control is going to work. Fortunately, there are softer alternatives available (e.g., bifenazate, pymetrozine). The progressive introduction of these to Washington hop production will enhance the prospects of successfully using biological control as an integral part of hop pest management.

Improving the Battlefield

We still have much to learn about the biological details of natural enemy warfare in hop yards and how best to manage it for optimum results. It is likely that making the “battlefield” a good place for predators to live will be critical. This season we will begin to look at the potential of using ground covers with nutritional and/or protective benefits for the army in our Prosser hop yard. For example, the nectar of some ground covers like vetch and buckwheat have high nutritive value that may help increase or sustain populations of predatory minute pirate bugs and big-eyed bugs. Ground covers may also have benefits for hop plant nutrition as well as reducing dustiness in hop yards, a factor that promotes spider mite populations.

Ensuring sustainability is crucial to long-term success of biological control. While chemical weapons often have a significant and increasing price tag, the natural army of predators is a free resource provided by Mother Nature. Hop growers should take the opportunity to command this army in their own operation, letting freedom (from pests) ring.

Dr. David James is an Entomologist with WSU’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center (IAREC) in Prosser and a frequent contributor to AENews. He can be reached at (509) 786-2226 or djames@tricity.wsu.edu.

REFERENCES

1. Campbell, C. A. M. and R. Lilley. 1999. The effects of timing and rates

of release of Phytoseiulus persimilis against two-spotted spider mite

Tetranychus urticae on dwarf hops. Biocontrol Science & Technology

9: 453-465.

2. Ehler, L. E. 1992. Guild analysis in biological control. Environmental

Entomology 21: 26-40.

3. James, D. G. and Price, T. C. 2000. Abamectin resistance in mites on

hops. Agrichemical and Environmental News 170: 4-5. (http://aenews.wsu.edu/June00AENews/June00AENews.htm#anchor5232326)

4. James, D. G. 2001. Pesticide safety and beneficial arthropods. Agrichemical

and Environmental News 188: 8-12. (http://aenews.wsu.edu/Dec01AENews/Dec01AENews.htm#anchor432738)

5. James, D. G., T. S. Price, L. C. Wright, and J. Perez. 2001. Mite abundance

and phenology on escaped and commercial hops in Washington State, USA.

International Journal of Acarology 27: 151-156.

6. Murdoch, W. W., J. Chesson and P. L. Chesson. 1985. Biological control

in theory and practice. American Naturalist 125: 344-366.

7. Pruszynski, S. and W. W. Cone. 1972. Relationships between Phytoseiulus

persimilis and other enemies of the twospotted spider mite on hops.

Environmental Entomology 1: 431-433.

8. Riechert, S. E. and Lawrence, K. 1997. Test for predation effects of

single versus multiple species of generalist predators: spiders and their

insect prey. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 84: 147-155.

Return to Table of Contents for the June 2002 issue

Return to Agrichemical and Environmental News Index

Return to PICOL (Pesticide Information Center On-Line) Home Page

Defusing Diffuse KnapweedBiological Control of an Explosive Weed |

Click here for PDF version of this document (recommended for printing). Should you not have Adobe Acrobat Reader (required to read PDF files), this free program is available for download at http://www.adobe.com/prodindex/acrobat/readstep.html |

Dale K. Whaley and Dr. Gary L. Piper, WSU

Diffuse

knapweed, Centaurea diffusa, a member of the plant family Asteraceae,

is believed to have been accidentally introduced into Washington State

during the early 1900s as a contaminant of alfalfa seed imported from

Eurasia. The plant has since spread to infest nearly a half million acres

across all counties east of the Cascade Mountains. It is also prevalent

in many western Washington counties. Nearly 90% of the infested land lies

in six counties bordering the Columbia River to the north and east: Okanogan,

Ferry, Stevens, Chelan, Kittitas, and Yakima. Based upon the weed’s

calculated 17.8% annual rate of spread, about 12 million acres remain

potentially susceptible to knapweed invasion during the next few decades.

Diffuse

knapweed, Centaurea diffusa, a member of the plant family Asteraceae,

is believed to have been accidentally introduced into Washington State

during the early 1900s as a contaminant of alfalfa seed imported from

Eurasia. The plant has since spread to infest nearly a half million acres

across all counties east of the Cascade Mountains. It is also prevalent

in many western Washington counties. Nearly 90% of the infested land lies

in six counties bordering the Columbia River to the north and east: Okanogan,

Ferry, Stevens, Chelan, Kittitas, and Yakima. Based upon the weed’s

calculated 17.8% annual rate of spread, about 12 million acres remain

potentially susceptible to knapweed invasion during the next few decades.

The plant is well adapted for survival in disturbed, semiarid environments

as typified by degraded rangeland and pasture, fallow land, neglected

residential and industrial properties, gravel pits, clearcuts, river and

ditch banks, and transportation rights-of-way. Diffuse knapweed is a strong

competitor for water and nutrients, and the plant’s dense, spiny

overstory reduces availability of more desirable forage species to grazing

animals by as much as 90%. Dense infestations of the weed also restrict

access to or diminish the visual appeal of recreational lands, lower property

values, increase soil erosion rates, and provide fuel for late summer

and early fall wildfires.

Life Cycle and Traits

Diffuse knapweed can be classified as either a biennial or short-lived perennial with a well-developed taproot. It exhibits a preference for well-drained, light-textured soils and is intolerant of flooding or dense shade. The plant overwinters as a rosette of deeply divided leaves or as seed in the soil. Seeds germinate in the fall or spring when environmental conditions are favorable. The overwintered rosettes bolt during May of the second year of growth to produce plants characterized by upright, diffusely branched architecture and small, stalkless stem leaves. Plants stressed by drought, grazing, mowing, or some other form of physical disturbance may exhibit short-lived perennial characteristics. Diffuse knapweed flowers are usually white, but may be rose-purple or lavender. Flowering occurs from July to September. Flower heads are solitary or borne in clusters of two to three at the ends of the branches. Each head bract is edged with a fringe of small spines and tipped with a pronounced spine.

Diffuse knapweed reproduces by seed. Depending on moisture availability, each plant can develop from 1,000 to 18,000 seeds. Mature, seed-laden plants can be transported long distances when they become attached to the undercarriages of vehicles and equipment. When plants are broken at ground level by vehicles or wind, they can become tumbleweeds, dispersing seeds along transportation corridors. Such windblown plants may enter rivers, streams, and irrigation canals, where they may continue to move many miles before washing ashore. The seeds also can be carried in mud clinging to footwear, tires, and vehicles, and can be dispersed by wildlife foraging activity. Movement of contaminated forage and feed grains by livestock producers has also contributed to the weed’s widespread distribution.

Herbicides can control diffuse knapweed short-term,

but successful long-term management cannot rely upon repeated chemical

applications. The weed’s seed output is enormous and its infestations

are extensive, frequently occupying lands that are difficult to access

and/or of low value. Herbicide purchase and application are costly and

can raise environmental concerns. Any long-term, economical, and environmentally

sound solution to diffuse knapweed suppression must involve an integrated

management approach wherein biological control organisms are deployed

along with a more judicious use of herbicides and other suppressive strategies.

Biological control is the planned use of various natural enemies to reduce

the vigor, reproductive capacity, or effect of a pest—in this case,

a weed. The technique is based on the premise that the attack of natural

enemies stresses the pest population, eventually reducing its density.

Biological control efficiency against weeds is dependent upon the type

and number of control organisms present, their time of attack in relationship

to the weed’s growth cycle, the amount of damage inflicted, and the

competitive abilities of the replacement vegetation.

During the last quarter century, Agriculture Canada (now Agriculture and

Agri-Food Canada), the International Institute of Biological Control (now

CAB Bioscience), the United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural

Research Service (USDA-ARS) and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service

(USDA-APHIS), and several state universities have developed programs to

find, evaluate, and introduce biological agents for the control of diffuse

knapweed and its relatives. As a result of these combined efforts, a complex

of exotic, host-specific root- and seed head-feeding insects have been

identified, acquired, and released into North America for knapweed suppression.

Root-infesting bioagents include the beetles Cyphocleonus achates

and Sphenoptera jugoslavica, and the moth Agapeta zoegana.

Seed head-attacking insects include the beetles Bangasternus fausti,

Larinus minutus, and L. obtusus, the flies Chaetorellia

acrolophi, Urophora affinis, and U. quadrifasciata,

and the moth Metzneria paucipunctella. All of these organisms are

important in reducing diffuse knapweed vigor and reproductive output,

but one in particular has proven to be highly effective in rapidly suppressing

populations of the weed. That insect is the lesser knapweed flower weevil,

L. minutus.

Weevil

Superstar

Weevil

Superstar

Larinus minutus was imported from Greece and

first released in Washington in 1991. During the last decade, the beetle

has been raised by university, USDA, and other weed management personnel

at nursery sites within the state. Upon translocation into most counties

in eastern Washington, L. minutus has readily established itself.

The insect prefers to attack diffuse knapweed but will also successfully

utilize spotted knapweed (Centaurea maculosa) and meadow knapweed

(C. pratensis) as hosts.

Adults are active in the field from mid-May to early August. Upon emergence

from their overwintering sites in the spring, the adults are one-quarter-inch

long, have a large snout with chewing mouth parts, and are a golden to

rust-brown color. As the beetles age, they become dark brown or black.

Adults will congregate, often in massive numbers, beneath the leaves and

in and around the root crowns of the rosettes, where they feed. Several

dozen beetles can totally defoliate and subsequently kill an averaged-sized

rosette in less than a week. Once the plant initiates stem development,

the beetles will feed on the stems, branches, leaves, and immature flower

buds. Such feeding can kill the plant or cause pronounced stunting and

flower head deformation. These injured plants assume a bluish-green or

gray color and are easily detected in a knapweed stand.

Adult

weevils are very active, readily moving many miles in search of knapweed.

Mating begins approximately four weeks after the initial emergence and

continues throughout the duration of their adult lives. Females feed on

knapweed flowers and pollen to acquire nutrients necessary for egg production.

They lay their eggs among the featherlike structures known as pappus hairs

on the opened flower heads. Each female can produce between 28 and 130

eggs during her lifetime, averaging 66. Up to seven eggs may be laid in

a single day. The eggs have a three-day incubation period. Newly emergent

larvae feed on the pappus hairs; subsequent larval instars feed on the

developing seeds and receptacle tissue of the flower head. A single L.

minutus larva, during its four-week developmental period, is capable

of consuming all of the seeds in a diffuse knapweed head. The larvae may

also eat the immature stages of other insect species found within the

head. In areas where the weevil is well established, L. minutus

larvae can readily destroy every seed head in a stand of knapweed.

Adult

weevils are very active, readily moving many miles in search of knapweed.

Mating begins approximately four weeks after the initial emergence and

continues throughout the duration of their adult lives. Females feed on

knapweed flowers and pollen to acquire nutrients necessary for egg production.

They lay their eggs among the featherlike structures known as pappus hairs

on the opened flower heads. Each female can produce between 28 and 130

eggs during her lifetime, averaging 66. Up to seven eggs may be laid in

a single day. The eggs have a three-day incubation period. Newly emergent

larvae feed on the pappus hairs; subsequent larval instars feed on the

developing seeds and receptacle tissue of the flower head. A single L.

minutus larva, during its four-week developmental period, is capable

of consuming all of the seeds in a diffuse knapweed head. The larvae may

also eat the immature stages of other insect species found within the

head. In areas where the weevil is well established, L. minutus

larvae can readily destroy every seed head in a stand of knapweed.

Mature larvae construct egg-shaped pupal chambers from seed fragments and pappus hairs within the damaged heads. Adults exit from the heads from mid-July to mid-August by chewing out a round hole at the top of the pupal cell. These hollowed-out heads are highly visible, providing a means to quickly assess the occurrence and extent of the beetle population. Adults feed on knapweed foliage for several weeks before seeking out sheltered overwintering sites. One generation is completed per year in Washington.

Biological Control Outlook

Larinus minutus is a highly effective biological control agent. It is unequivocally the most destructive of all the insects released against knapweed in North America thus far. It readily survives in most sites where released, develops huge populations, and is capable of severely impacting a weed population within three to five years after being released. We urge anyone plagued by diffuse knapweed to acquire and release this beetle on lands under their supervision. (For information on acquiring the beetle, contact the authors of this article.)

The goal of any biological control program is to shift the competitive balance away from the target weed to desirable grasses and forbs. The intended outcome is the return of weed-dominated lands to more diverse and productive plant communities. In areas where L. minutus activity is pronounced, this goal is being realized with respect to diffuse knapweed.

Dale Whaley (dwhaley@wsunix.wsu.edu or 509-335-5818) and Gary Piper (glpiper@wsu.edu or 509-335-1947) are with the Department of Entomology at Washington State University in Pullman where they conduct research on biological control of weeds.

Return to Table of Contents for the June 2002 issue

Return to Agrichemical and Environmental News Index

Return to PICOL (Pesticide Information Center On-Line) Home Page

FEQL Advisory Board Meets |

Click here for PDF version of this document (recommended for printing). Should you not have Adobe Acrobat Reader (required to read PDF files), this free program is available for download at http://www.adobe.com/prodindex/acrobat/readstep.html |

Dave Winckler, Incoming Chair, FEQL Advisory Board

The Food and Environmental Quality Laboratory (FEQL) at Washington State University (WSU) held its spring Advisory Board meeting on Wednesday, April 17, 2002, on the Tri-Cities campus of WSU. Highlights of this meeting included changes in board members and officers, restructuring of meeting format, and reports by FEQL faculty. Board chair Marilyn Perkins opened the meeting at 9:10 a.m.

Background

The FEQL was mandated by the Washington State Legislature to focus research and extension efforts on all aspects of crop protection technologies across the state. The need for such a WSU facility grew out of two concerns: potentially devastating losses of crop protection tools for the minor crops characteristic of Washington agriculture and the safety of these tools to human health and the environment. In accordance with the founding legislation, FEQL is advised by a board of stakeholders representing a number of distinct functions pertaining to Washington State agriculture. Board members generally serve three-year terms, with new officers elected annually.

Changes to the Board

The board recognized Scott McKinnie’s service as inaugural chair of the board by presenting him with a framed certificate. McKinnie, of Far West Agribusiness Association, holds the Chemical and Fertilizer Representative seat on the board and served as president before Marilyn Perkins. Perkins is with the League of Women Voters and holds the Consumer seat.

Dr. James Zuiches, Dean of the WSU College of Agriculture and Home Economics, explained that he had appointed Ralph Cavalieri to replace him on the FEQL advisory board. This move comes in response to recognition that the original legislative intent of this position on the advisory board was to represent Washington State University’s research function. Dr. Cavalieri’s position as Director of WSU’s Agricultural Research Center makes him a very appropriate board member. Dr. Zuiches becomes an ex-officio board member.

The terms of Marilyn Perkins, Matthew Keifer, Royal Schoen, Gregg Möller, Dave Winckler, and Barbara Morrissey were all scheduled to expire June 30, 2002, but all present members agreed to accept appointment to another term. Keifer is with the Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center and holds the board’s position for a Health Professional/Human Toxicologist. Schoen is with the Washington State Department of Agriculture and holds the board position reserved for that governmental body. Möller, from the University of Idaho, fills the board’s position for an Oregon or Idaho Laboratory representative. Winckler, with the Washington State Farm Bureau, holds the position of Farm Organization representative. Morrissey holds the Washington State Department of Health seat.

The board elected new officers for the coming year. Dave Winckler will serve as the next chair and Ann George as vice-chair for the Advisory Board. George is with the Washington Hop Commission and holds the position of Washington State Commission on Pesticide Registration representative to the FEQL board. Winckler’s and George’s terms begin July 1, 2002.

Budget Update

Dean Zuiches explained the impacts of recent state budget cuts on higher education in general and Washington State University in particular. The net result of the various reductions is a cut of $17 million to the university. Budget cuts will be required throughout the university, including an approximate $1.2-1.5 million cut to the College of Agriculture and Home Economics. Zuiches also outlined some of the positive things that are happening in the university, including the completion of strategic plans throughout the various departments and initiatives that are underway toward development and strengthening of programs in enology and viticulture, biologically intensive and organic agriculture, and watershed management and water quality.

Faculty Accomplishment Reports

In the interest of time and thoroughness, FEQL faculty members Catherine Daniels, Allan Felsot, Vincent Hebert, and Doug Walsh had prepared statements detailing their accomplishments of the past six months. These statements had been distributed to board members in advance of the meeting so they would have a written record of this material for passing along to their constituencies and so they would have an opportunity to formulate questions for faculty members.

Discussion of Dr. Catherine Daniels’ accomplishments included feedback on the Pesticide Information Center (PIC) newsletter, Agrichemical and Environmental News. The newsletter became an exclusively electronic publication in January 2002 (after thirty years as a print publication and six years on-line). Members expressed uniform satisfaction with the enhancements in the electronic edition. Daniels’ program also includes development of crop profiles (http://www.tricity.wsu.edu/%7Ecdaniels/wapiap.html or #CropProfiles). The board expressed satisfaction with the content and utility of these profiles and questioned why more of them are not produced. Discussion ensued about how important and useful crop profiles are and why more of them aren’t produced. PIC staff stands ready to assist in the production of crop profiles, but growers and commodity groups often don’t seem to recognize the full value of producing these detailed pest management reports.

Dr. Doug Walsh reported that he has been assigned a laboratory at the Prosser Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center (http://www.prosser.wsu.edu/). Of Walsh’s many field research projects, he spoke of his success in procuring grants and conducting research on buffer zones. Technically a field entomologist, he works closely with growers in a number of commodities including mint, hybrid poplars, and wine grapes. Walsh has also been working with WSU virologist Dr. Gary Grove to include disease research as well as insect research on these crops. He is also working on a project with Dr. Fran Pierce, Director of the Center for Precision Agricultural Systems. A grant from American Farmland Trust has enabled CPAS to establish a site-specific weather network through which weather data is monitored and shared among a network of growers. This network model may be applicable to insect and other research. Walsh also spoke about last year’s study among apple thinners and cherry pickers for carbaryl (Sevin) and AZM (Guthion) residues, enlightening the board about a number of practical concerns when conducting on-site residue testing with humans.

Dr. Vince Hebert

talked about his first year and a half with FEQL, emphasizing the infrastructure-building

process in which he has engaged over the past eighteen months, especially

bringing the FEQL analytical laboratory facility to Good Laboratory Practice

(GLP) standards and establishing functional working partnerships with

industry and Federal/state agencies. Regarding specific projects, his

IR-4 (Interregional Research Project #4 minor crops protection) studies

have been completed ahead of schedule. Two magnitude-of-residue studies

have been completed, written, submitted, and approved; a third is completed

and being written at this time. This year, Hebert will be involved in

a pesticide spray drift exposure study in cooperation with Dr. Richard

Fenske at the University of Washington. The study will use global positioning

technology (GPS) to track movements of twelve children within their home

and community toward defining real-life exposures and associated risks.

Subjects and their environments will be monitored (via urine testing,

hand wipes, air sampling, dust sampling, etc.) following spraying of nearby

fields. Hebert and his staff will also be involved in a study examining

the kinetic behavior of aged pheromone dispensers. Pheromone mating disruption

has become a major component of codling moth control in Pacific Northwest

apple orchards. In cooperation with Jay Brunner at the WSU Tree Fruit

Research and Extension Center, FEQL will monitor and analyze the release

rates from dispensers at various ages. In keeping with Dr. Hebert’s

area of specialization, atmospheric transport, he will also examine the

fate of the released pheromones.

Allan Felsot distributed a handout on his study of the effects of the

number of spray applications on azinphos-methyl (AZM) residues in composite

and single serving apples and a copy of a journal article he published

in Toxicology (http://aenews.wsu.edu/June02AENews/FEQLReport/FelsotToxicologyArticle.pdf

). Felsot discussed his transgenic crops research, explaining that not

all research takes place in a laboratory; some of his work involves reviewing

and elucidating existing research. He also told the board about a new

research project on sprayer technology funded for crop year 2002 by the

Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission. Enhancing application efficiency

is one path toward reducing production costs as well as reducing human

health hazard. This project will investigate the relative efficiency of

various spray technologies in an effort to determine the most efficient

equipment, the minimum effective application rate, residue deposition,

better means of determining worker hazard, and methods that minimize drift.

Carol Ramsay, WSU Pesticide Education Specialist, gave the board an update on a Cooperative Extension opportunity via conference call from Pullman. Because of the success of Ramsay’s past Pesticide Issues Conferences, she has been asked by University of Washington to take the lead on co-hosting a pesticide issues conference. Where Ramsay’s conference had generally been held in the fall, a later date is being targeted for this new conference in order to give late-maturing crop (e.g., orchard) growers a better opportunity to participate. The date proposed is February 26, 2003. An advisory committee is being assembled. The tentative conference theme is “Agriculture and Health Issues.” Anyone with suggestions for conference advisors should contact Ramsay at ramsay@wsu.edu or (509) 335-9222.

Advisory Board Survey

In an effort to streamline the important interface of the advisory board with FEQL faculty, a survey of board members was conducted last winter. The following items were agreed upon:

- On the balance, twice a year, full-day meetings in Tri-Cities seemed to be the best frequency, duration, and location.

- The FEQL faculty appreciates and respects the board in its advisory capacity. They take the comments of the board into serious consideration when pursuing the overall mission and functions of FEQL and PIC.

- The board is a valuable communication hub. Not only do FEQL and WSU internalize the opinions of the advisory board, advisory board members take the information about FEQL activities back to their constituencies.

- In response to suggestions from the board, this advisory board meeting was organized around a theme (worker exposure). As this seemed to be a very successful meeting, discussion ensued on possible themes for future meetings. Water quality was mentioned as one possibility.

The next meeting of the FEQL Advisory Board is scheduled for October 23, 2002.

Dave Winckler is a Project Director with the Washington State Farm Bureau. He begins his term as chair of the FEQL Advisory Board July 1, 2002. For questions about the FEQL or its board, contact FEQL support staff members Doria Monter-Rogers at monter@tricity.wsu.edu or (509) 372-7462 or Sally O’Neal Coates at scoates@tricity.wsu.edu or (509) 372-7378.

Announcements & Upcoming ConferencesIR-4 Seeks Input for 2002 Prioritization WorkshopThe Interregional Research Project Number 4 (IR-4) was established in 1963 to increase the availability of crop protection chemistries for minor crop producers. IR-4 is a federal/state/private cooperative that aspires to obtain clearances for pest control chemistries on minor crops. Each year, dozens of new projects are undertaken by IR-4. The program receives a far greater number of requests than it can pursue, so projects are prioritized, and only the higher-priority projects are guaranteed investigation. The prioritization process takes place at an annual meeting. The IR-4 prioritization workshop for year 2002 projects will take place September 17, 18, and 19 in Orlando, Florida. Commodity representatives and growers who may be interested in helping to identify and prioritize the IR-4 projects (pesticides for residue research on specific commodities) for 2003 should fill out a Project Clearance Request form (located at the IR-4 Web site at URL http://www.cook.rutgers.edu/~ir4) and contact Washington State IR-4 Liaison Dr. Douglas B. Walsh. By providing Dr. Walsh with efficacy data and an explanation of the industry's need for a particular product, you can help him and the Western Region IR-4 program function as advocates for that product. If you have questions regarding the prioritization process, or would like to express a pesticide/commodity need for registration please contact Dr. Doug Walsh at (509) 786-2226 or dwalsh@wsu.edu. NOTICE OF VACANCYExtension Coordinator Specialist, Integrated Pest ManagementPosition #87641 Location: Washington State University, Prosser, Washington Position: This full-time position is a key member of the WSU Integrated Pest Management Program (IPM) and is responsible for managing and coordinating various aspects of IPM for the state of Washington. The IPM Extension Coordinator Specialist will assist the IPM Coordinator to develop, promote, implement, and document IPM projects and programs in collaboration with WSU researchers, extension personnel, and other affected public or private organizations. Rank and Salary: This position is Administrative/Professional rank, 1.0 FTE, 12 month, Temporary position (Monday-Friday, 8am-5pm). Salary is competitive and commensurate with training and experience. Duties and Responsibilities: May include any or all of the following: performing comprehensive programmatic development, leading research initiatives, grant writing, facilitating university-based outreach efforts, and providing expertise in the area of integrated pest management in agriculture, landscape, and ecologically sensitive ecosystems. The individual in this position will also, on occasion, represent the Coordinator (in his absence) in both internal and external matters. The successful candidate is expected to possess demonstrated expertise in the development and application of pest management strategies and possess general knowledge of the principles and practices underlying integrated pest management. Qualifications

Organization and Location: Washington State University Cooperative Extension, Prosser, Washington. Washington State University is a Land Grant, comprehensive research, and cooperative extension institution. The Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center (IAREC) of Washington State University at Prosser, (WSU Prosser IAREC), is the focal point for research, extension, and certification programs that address the concerns of irrigated agriculture in Washington State. Visit our website at http://www.prosser.wsu.edu Application

Process: Screening of application materials begins July,

8, 2002, and will continue until the position is filled. Send

Letter of application, resume, transcripts, three current letters

of reference (dated within the past year) to: Dr. Douglas Walsh,

Search Chair, Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center,

Washington State University, 24106 N. Bunn Rd., Prosser, WA 99350-9212 Washington State University is an Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action educator and employer. Women, ethnic minorities, Vietnam-era or disabled veterans, persons of disability and/or person age 40 and over are encouraged to apply. Washington State University employs only U.S. Citizens and lawfully authorized non-U.S. citizens. All new employees must show employment eligibility verification as required by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service. Accommodations for applicants who qualify under the Americans with Disabilities Act are available upon request. Foss and Ramsay Receive GrantWashington

State University Extension Coordinators and Education Specialists

Carrie Foss and Carol Ramsay have been awarded a grant from the

United States Environmental Protection Agency for Consumer Pesticide

Use Reduction. The editors of AENews encourage readers to check out the Hortsense Web site--a useful and user-friendly tool for home gardeners in Washington State. The

3rd Annual Conference on Pesticide Stewardship

|