October 2003, Issue No. 210

A monthly report on

environmental and pesticide related issues

A monthly report on environmental and pesticide related issues

Open Forum: In an attempt to promote free and open discussion of issues, Agrichemical and Environmental News encourages letters and articles with differing views. To discuss submission of an article, please contact Dr. Allan Felsot at (509) 372-7365 or afelsot@tricity.wsu.edu; Dr. Catherine Daniels at (253) 445-4611 or cdaniels@tricity.wsu.edu; Dr. Doug Walsh at (509) 786-2226 or dwalsh@tricity.wsu.edu; Dr. Vincent Hebert at (509) 372-7393 or vhebert@tricity.wsu.edu; or AENews editor Sally O'Neal Coates at (509) 372-7378 or scoates@tricity.wsu.edu. EDITORIAL POLICY, GUIDELINES FOR SUBMISSION.

Go to Agrichemical and Environmental News Index

Go to WSPRS (Washington State Pest Management Resource Service) Home Page

FEQL Reviews a Decade of Service

FEQL Faculty, Washington State University

In October 1993, the Food and Environmental Quality Laboratory (FEQL) held a grand opening reception at its new facility on the Tri-Cities campus of Washington State University (WSU). This month marks the tenth anniversary of the lab’s official opening, and provides today’s faculty an opportunity to review the lab’s accomplishments over the past decade.

Legislative Mandate

In 1991, the Washington State Legislature mandated creation of the Food and Environmental Quality Laboratory. The wording of the Revised Code of Washington (RCW 15.92.050) is quite specific:

A food and environmental quality laboratory operated by Washington State University is established in the Tri-Cities area to conduct pesticide residue studies concerning fresh and processed foods, in the environment, and for human and animal safety. The laboratory shall cooperate with public and private laboratories in Washington, Idaho, and Oregon.

The following article, RCW 15.92.060, enumerates the laboratory’s responsibilities:

- Evaluating regional requirements for minor crop registration through the federal IR-4 [Interregional Research #4] program;

- Providing a program for tracking the availability of effective pesticides for minor crops, minor uses, and emergency uses in this state;

- Conducting studies on the fate of pesticides on crops and in the environment, including soil, air, and water;

- Improving pesticide information and education programs;

- Assisting federal and state agencies with questions regarding registration of pesticides which are deemed critical to crop production, consistent with priorities established in RCW 15.92.070; and

- Assisting in the registration of biopesticides, pheromones, and other alternative chemical and biological methods.

Soon after the state legislature handed down this mandate, Washington State University began the process of creating an infrastructure for the new lab, which included developing the necessary faculty positions and remodeling and equipping the physical facility on the Tri-Cities campus.

Responsibility 1: IR-4 and Minor Crop Registrations

The IR-4 component of FEQL research is divided into two sections: field testing and laboratory residue analysis. The regional IR-4 office assigns specific field trials for crops grown in the Pacific Northwest, while laboratory trials are assigned based on lab expertise with a specific crop or chemical. Faculty have been very successful in the last ten years in obtaining assignments for both field trial and lab analyses; the data submitted from those experiments have resulted in important minor crop registrations for Washington commodities. All of the work is completed under Good Laboratory Practices, which are a set of exacting scientific and recordkeeping standards that require highly trained and motivated technicians and quality assurance staff.

This residue work continues to be an integral part of the FEQL research program. Each year IR-4 holds a Project Prioritization meeting where research requests gathered from across the nation are prioritized for field testing the following year. There are always many more requests than funding available for field trials. Our faculty assist Washington producers in submitting requests, then attend the annual Project Prioritization meeting to effectively communicate Washington growers’ needs. To date, faculty have been very successful in getting a number of Pacific Northwest requests prioritized, placed on the work plan, and completed through registration.

Responsibility 2: Pesticide Tracking

A program for tracking the availability of pesticides for minor crops, minor uses, and emergency uses in the state was initiated in 1997. The Pesticide Notification Network (http://www.pnn.wsu.edu) keeps growers up to date on new and revised pesticide labels and regulatory happenings through a targeted notification system and a Web page. This popular service is funded by the Washington State Commission on Pesticide Registration (http://wscrp.org) and is one of the three cornerstones of the FEQL extension program.

Responsibility 3: Environmental Fate

Pesticide fate encompasses a wide array of scientific disciplines. The philosophy of the FEQL faculty has always been to pursue research projects that (1) address issues of the highest concern to the agricultural community; (2) match the expertise and capabilities of the faculty, staff, and laboratory; and (3) will result in the greatest good for the most people. This philosophy is demonstrated in the diversity of research conducted and partnerships formed by FEQL over the past ten years. Pesticide fate studies were initiated in 1993 and as a subject area have continued to be a faculty focal point. FEQL faculty conducts applied scientific research as well as toxicological evaluations and risk assessments to assess the fate of pesticides in the environment and also to determine the potential consequences of exposure. The faculty’s combined expertise has resulted in numerous opportunities to assist our clientele and form partnerships. One such partnership is with the Washington State Department of Agriculture (WSDA), which requested that FEQL faculty become involved in herbicide drift issues. Early studies focused on contentious area-wide disputes in the Horse Heaven Hills area of Benton County. Faculty research demonstrated that herbicide applications on wheat were not responsible for injury found on neighboring yard plants or orchards. More recent studies focus on atmospheric herbicide drift onto high-value wine grapes in the Walla Walla area. Faculty are working with Drift Task Force representatives from Washington and Oregon to define and resolve the problem.

FEQL faculty have also conducted soil studies on the environmental fate of an insecticide using drip irrigation as an application method. Fate of pesticides in water is a critical issue. Faculty serve as advisors to surface and groundwater monitoring programs conducted by WSDA. Studies on alternative sprayer technologies have been performed to better understand chemical deposition patterns. The purpose of these studies is to optimize spray targeting, thereby reducing the amount of chemical applied, saving both money for industry and exposure to farmworkers and the environment. Other application methodologies studied by FEQL faculty include targeted barrier sprays, which have also met the objective of reduced product use.

An issue of concern to Washington growers in recent years has been the failure of pheromone dispensers used in mating disruption, a key element of integrated pest management (IPM) programs in tree fruit production. Faculty have been testing the environmental behavior of these dispensers to determine the chemical release rate and thus the effective life span of this important pest management tool. Other studies have focused on successfully switching an industry to “softer” pesticides that are more compatible with biological control programs.

Partnering with the Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health program at the University of Washington (UW), faculty have begun characterizing pesticide exposure to farm families in agricultural communities, particularly people living in residences adjacent to production fields. Other projects include spray drift modeling and determination of no spray buffer zones for protecting residences and sensitive habitat.

Responsibility 4: Information and Education

Pesticide information and education programs are the second cornerstone of the FEQL extension program. In the last ten years, FEQL faculty have given hundreds of talks and presentations to pesticide applicators, master gardeners, and the general public. They partner with other WSU and UW programs in advising, sponsoring, and speaking at the annual Pesticide Issues Conference, where the top state issues are discussed by experts at public forums. FEQL faculty have created the Washington State Pest Management Resource Service (WSPRS), an information hub providing outreach to audiences ranging from urban to small farm to homeowner to production agriculture. Information delivery tools developed by FEQL and WSPRS have included databases (http://picol.cahe.wsu.edu/LabelTolerance.html), extension bulletins, newsletters (http://aenews.wsu.edu/), fact sheets, and Web pages (http://wsprs.wsu.edu/, http://feql.wsu.edu/, and http://ipm.wsu.edu/). Topics include all aspects of pest management, including cultural, biological, organic and, conventional pesticide tools.

Responsibility 5: Agency Interface

Assisting federal and state agencies with questions regarding registration of pesticides that are deemed critical to crop production is the third cornerstone of the FEQL extension program. Toward fulfillment of the 1996 Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA) requirements for the reregistration of pesticides, faculty and staff collect information about local use practices, critical needs, and grower comments, then communicate that information to WSDA, USDA, and EPA. At the same time, faculty apprise the state's grower community of EPA regulatory concerns and relevant USDA programs that can assist in addressing their critical needs.

One way in which we communicate pest management practices and critical needs is through the production of Crop Profiles and Pest Management Strategic Plans. These documents, requested by USDA, are utilized by state and federal agencies to communicate actual use of and critical gaps in pest management tools for specific crops in individual states or geographic regions.

Responsibility 6: Alternative Methodologies

Faculty assist in the registration of biopesticides, pheromones, and other alternative chemical and biological methods through the IR-4 program and the WSU IPM program. Much of the work described under Responsibilities 1 and 3, above, is directed at evaluating and supporting alternative methodologies.

Beyond the specific mandates of the founding legislation, the FEQL faculty participate in activities such as teaching, graduate student advising and mentoring, publication in scientific journals, grantsmanship, and service (committee) work. They are highly interactive with other units within and without WSU. In accordance with the founding legislation, FEQL faculty are advised by a board of stakeholders representing the distinct facets of PNW agriculture.

The Food and Environmental Quality Laboratory is proud of its first decade of service. In accordance with its mission statement, “The FEQL works to ensure the quality and safety of food, the long-term sustainability of our food-producing lands and surrounding environment, and the economic viability of the agricultural and food industries of Washington State.” We look forward to continuing to fulfill this mission in the next decade and beyond.

For more information on the Food and Environmental Quality Laboratory or the Washington State Pest Management Resource Service, point your Internet browser to their respective Websites at http://feql.wsu.edu or http://wsprs.wsu.edu. Dr. Allan S. Felsot, FEQL Environmental Toxicologist, can be reached at (509) 372-7365 or afelsot@tricity.wsu.edu. Dr. Catherine H. Daniels, WSU Pesticide Coordinator and WSPRS Director, can be reached at (253) 445-4611 or cdaniels@tricity.wsu.edu. Dr. Douglas B. Walsh, Agrichemical & Environmental Education Specialist, IPM Coordinator, and IR-4 Liaison, can be reached at (509) 786-2226 or dwalsh@wsu.edu. Dr. Vincent R. Hebert, Analytical Chemist, can be reached at (509) 372-7393 or vhebert@tricity.wsu.edu.

Go to this issue's Table of Contents

Go to Agrichemical and Environmental News Index

Go to WSPRS (Washington State Pest Management Resource Service) Home Page

Tiny Shrimp Present Jumbo Problem

Soft Market and Loss of Carbaryl Threaten to Swamp Oyster Growers

Dr. Kim Patten, Horticulturist and Extension Specialist, WSU

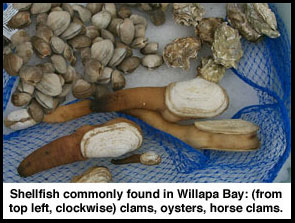

Two of Washington State’s largest coastal estuaries, Willapa Bay and Grays Harbor, support a multi-million dollar shellfish industry. They produce Japanese oysters on approximately 9,900 acres of aquatic tidelands, or approximately 19% of those bays’ intertidal land. This is about 23% of the oysters produced in the United States and 66% of those produced in the State of Washington.

Besides

their roles as two of the major oyster-producing bodies of water in the

nation, these estuaries are of great ecological significance. They are

highly productive critical habitats for migratory wildfowl and endangered

and threatened species of fish. Both estuaries are among the ten major

wintering and resting areas for waterfowl and shorebirds of the Pacific

Flyway, often hosting more than 100,000 shorebirds at a time. Similarly,

these estuaries support large beds of eelgrass and are the spawning, rearing,

and/or feeding grounds of numerous fish and other marine species, including

coastal cutthroat trout, five species of salmon, Pacific herring, English

sole, sturgeon, and Dungeness crab.

Besides

their roles as two of the major oyster-producing bodies of water in the

nation, these estuaries are of great ecological significance. They are

highly productive critical habitats for migratory wildfowl and endangered

and threatened species of fish. Both estuaries are among the ten major

wintering and resting areas for waterfowl and shorebirds of the Pacific

Flyway, often hosting more than 100,000 shorebirds at a time. Similarly,

these estuaries support large beds of eelgrass and are the spawning, rearing,

and/or feeding grounds of numerous fish and other marine species, including

coastal cutthroat trout, five species of salmon, Pacific herring, English

sole, sturgeon, and Dungeness crab.

Both the ecology of these estuaries and the shellfish industry they support are being seriously threatened by expansive growth of several nonnative invasive species (Spartina grass, European green crab, and Japanese eelgrass), and native pests (burrowing shrimp and oyster drills). Spartina and burrowing shrimp are by far the most serious concerns. Spartina has been discussed in previous issues of this newsletter (see “Nothin’ Could be Fina’ than the Killin’ o’ Spartina,” AENews August 2002, Issue No. 196 and “Evaluating Imazapyr in Aquatic Environments,” AENews May 2003, Issue No. 205).

Burrowing

shrimp, including ghost shrimp (Neotrypaea californiensis) and

mud shrimp (Upogebia pugettensis) re-suspend sediment in the

process of feeding and of constructing and maintaining burrows. This results

in a continuous mixing of deep and shallow layers of sediment (bioturbation),

which causes surface organisms (eelgrass to oysters) to literally sink

and die. In Willapa Bay, it is estimated that 15,000 to 20,000 of the

bay’s 80,000 acres (45,000 of which are intertidal) are dominated

by burrowing shrimp. Over 3,000 acres of privately owned oyster growing

tidelands are estimated to have been permanently destroyed for not only

oyster culture but also as habitat for nearly all other estuarine biota,

including eelgrass, clams, and other sediment-dwelling organisms.

Burrowing

shrimp, including ghost shrimp (Neotrypaea californiensis) and

mud shrimp (Upogebia pugettensis) re-suspend sediment in the

process of feeding and of constructing and maintaining burrows. This results

in a continuous mixing of deep and shallow layers of sediment (bioturbation),

which causes surface organisms (eelgrass to oysters) to literally sink

and die. In Willapa Bay, it is estimated that 15,000 to 20,000 of the

bay’s 80,000 acres (45,000 of which are intertidal) are dominated

by burrowing shrimp. Over 3,000 acres of privately owned oyster growing

tidelands are estimated to have been permanently destroyed for not only

oyster culture but also as habitat for nearly all other estuarine biota,

including eelgrass, clams, and other sediment-dwelling organisms.

When

an aquatic area is dominated by burrowing shrimp, the sediment simply

becomes too soft to support commercial oyster production. Since the 1960s,

burrowing shrimp have been controlled by applying carbaryl, a carbamate

insecticide. These applications are not without controversy. Concerns

have been raised by numerous stakeholders about the use of carbaryl in

Willapa Bay and Grays Harbor, with respect to effects on non-target species

like Dungeness crabs and fish. There are also chemical trespassing issues.

As a result of these concerns, the oyster industry has been under intense

scrutiny by federal and state regulatory agencies, the local Shoalwater

Native American tribe, and environmental groups. The industry has been

looking for alternative controls in recent years, while incorporating

integrated pest management (IPM) principles into their control program.

As the result of these proactive efforts, the use of carbaryl has decreased.

Fewer than 800 acres were treated with this chemical last year, and growers

have carefully avoided treating any individual site within six years of

its last treatment. At this rate, however, growers are continuing to lose

ground to burrowing shrimp over time.

When

an aquatic area is dominated by burrowing shrimp, the sediment simply

becomes too soft to support commercial oyster production. Since the 1960s,

burrowing shrimp have been controlled by applying carbaryl, a carbamate

insecticide. These applications are not without controversy. Concerns

have been raised by numerous stakeholders about the use of carbaryl in

Willapa Bay and Grays Harbor, with respect to effects on non-target species

like Dungeness crabs and fish. There are also chemical trespassing issues.

As a result of these concerns, the oyster industry has been under intense

scrutiny by federal and state regulatory agencies, the local Shoalwater

Native American tribe, and environmental groups. The industry has been

looking for alternative controls in recent years, while incorporating

integrated pest management (IPM) principles into their control program.

As the result of these proactive efforts, the use of carbaryl has decreased.

Fewer than 800 acres were treated with this chemical last year, and growers

have carefully avoided treating any individual site within six years of

its last treatment. At this rate, however, growers are continuing to lose

ground to burrowing shrimp over time.

Yet these reductions were not enough to satisfy the stakeholders. To avoid costly legal battles brought on by lawsuits from the Washington Toxics Coalition, in April 2003 the oyster industry agreed to an out-of-court legal settlement to permanently phase out the use of carbaryl over a ten-year period.

Unfortunately for oyster producers, carbaryl is the only insecticide in use in U.S. marine waters. With no alternative control for burrowing shrimp in the foreseeable future and the continued spread of Spartina over prime shellfish tidelands, the fate of the $60 million Willapa and Grays Harbor oyster industry is in jeopardy.

The Washington State shellfish industry consists of mostly small and family-owned farms the economic viability of which is tenuous, based on a thin profit margin. Willapa oysters were Washington’s first export crop over 150 years ago. The shellfish industry is the largest employer and one of the key economic drivers in Pacific County. Along with other southwestern Washington counties already depressed from losses in forest and lumber-related industries, Pacific County has some of the highest unemployment rates and lowest per capita personal income in the state. The probable loss of the shellfish industry paints an even bleaker economic picture.

Making matters worse, market conditions for fresh-shucked-in-jar oysters are severely depressed. Increasing foreign competition and limited market alternatives cast a gloomy forecast for future grower returns. The combination of the loss of the industry’s ability to control their most significant pest, rapid spread of new pests, and the collapse of their market has positioned them in the “Perfect Storm.”

Numerous

research projects by WSU and other institutions to develop alternative

controls for burrowing shrimp are in progress. This includes testing alternative

“reduced-risk” insecticides and adjuvants, as well as alternative

insecticide delivery systems for those products, such as sub-surface shanking.

Several non-chemical methods are also being investigated, including both

biological and mechanical approaches. Mechanical methodologies being explored

include soil compaction and water jets to destroy shrimp burrows, both

of which are designed to expose shrimp to predation. Finally, an IPM project

is underway with the objective of pinpointing the population thresholds

that result in economic damage under various conditions. Given the economic

and ecological pressures brought to bear on this minor crop and the complexity

of its aquatic location, saving the industry presents a major challenge.

Numerous

research projects by WSU and other institutions to develop alternative

controls for burrowing shrimp are in progress. This includes testing alternative

“reduced-risk” insecticides and adjuvants, as well as alternative

insecticide delivery systems for those products, such as sub-surface shanking.

Several non-chemical methods are also being investigated, including both

biological and mechanical approaches. Mechanical methodologies being explored

include soil compaction and water jets to destroy shrimp burrows, both

of which are designed to expose shrimp to predation. Finally, an IPM project

is underway with the objective of pinpointing the population thresholds

that result in economic damage under various conditions. Given the economic

and ecological pressures brought to bear on this minor crop and the complexity

of its aquatic location, saving the industry presents a major challenge.

Dr. Kim Patten is the Station Manager for Washington State University’s Long Beach Research and Extension Unit. He can be reached at (360) 642-2031 or pattenk@cahe.wsu.edu.

Go to this issue's Table of Contents

Go to Agrichemical and Environmental News Index

Go to WSPRS (Washington State Pest Management Resource Service) Home Page

Searching for Alternatives to Plastic Mulch

Dr. Carol Miles, Lydia Garth, Madhu Sonde, and Martin Nicholson, WSU Vancouver Research and Extension Unit

The first man-made plastic was unveiled by Alexander Parkes in 1862. Since then, plastics have contributed to advances in medicine and healthcare, revolutionized packaging and products, and become commonplace in our homes, offices, schools, and almost every walk of our lives. Plasticulture, the use of plastics in agriculture, began in the 1950s. Agricultural uses for plastic include mulches, greenhouse elements, pots and plug trays, and irrigation pipe and tape. Since its introduction into agriculture, plastic has contributed significantly to the economic viability of farmers worldwide. The use of plastic mulch has become a standard practice for all vegetable farmers who benefit from weed control; reduced evaporation, fertilizer leaching and soil compaction; and elevated soil temperatures that promote earlier plant maturity.

Though very effective and affordable, plastic mulch has become an environmental management concern due to disposal issues. On-site disposal options such as open burning and dumping are environmental liabilities and recycling of dirty plastics is not an economically feasible option. The disposal option that most growers choose is the landfill. In 1999, almost 30 million acres worldwide were covered with plastic mulch, more than 185,000 of those acres were in the United States, and essentially all of this plastic entered the waste stream. An effective and affordable alternative to plastic mulch would contribute the same production benefits as plastic mulch and in addition would reduce non-recyclable and non-renewable waste. In 2003, we began to investigate alternatives to plastic mulch in vegetable production at Washington State University's (WSU's) Vancouver Research and Extension Unit.

Testing Six Mulches

Our study included six mulch treatments: Garden Bio-Film (corn starch), brown paper, paper + linseed oil, paper + tung oil, paper + soybean oil, and black plastic (control). The Bio-Film and paper (oiled or otherwise) are expected to degrade, thereby eliminating the waste problem associated with plastic mulch. In this study we used end rolls of 26 lb. kraft paper, similar to that used to make paper grocery sacks. End rolls are left over from industrial orders and their price varies seasonally. The purpose of the oil application is to reduce the rate of paper degradation in the field; it was unclear whether certain oils might prove more effective than others. A thin film of oil was applied evenly over the entire surface of the paper. Oil was sprayed onto the paper prior to laying the paper in the field so that the edges of the paper contacting the soil (the most likely site of degradation) would be coated with oil.

The experimental design of this study was a randomized complete block with four replications. Plots were 10 feet long and one (36-inch) bed wide, with 24 inches between beds. Two rows of drip tape were laid under the mulch treatments. Paper and plastic mulch were laid in the field using conventional mulch-laying equipment (Figure 1). Garden Bio-Film was laid by hand as the product we received from the manufacturer was packaged for home gardeners and was not compatible with our equipment. The manufacturer will package product for commercial use if there is demand. Two rows of six varieties of basil were transplanted in each plot on June 25 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1 |

FIGURE 2 |

|

|

Laying

paper mulch with conventional mulch-laying equipment; drip tape

was laid at the same time in two rows under the mulch. |

Basil

planted in two rows 10 feet long per plot; drip tape was laid under

the mulch along each row of basil. |

Findings: Four Performance Points

Following is a summary of our findings on four performance points for the six mulches tested: plant height, plant weight, temperature under the mulch, and condition of the mulch during and after its time in the field. We measured plant height and the quality of the mulches throughout the season and we measured plant fresh weight and plant dry weight at harvest. In August and September we measured temperature under some of the mulch treatments. In this study the six basil varieties differed significantly in height and weight but there was no interaction between variety and mulch treatment. That is, all six basil varieties responded in the same manner to each mulch treatment. Therefore we will only discuss the effects of mulch treatments on basil in general.

Plant Height. Plant height (cm) was measured weekly in August. There were some significant differences in plant height among the treatments; the Garden Bio-Film mulch treatment resulted in the tallest plants throughout the growing season (Table 1). Plant height in the paper mulch treatments did not differ significantly from plant height in the black plastic mulch treatment except during the second week. Additionally, the type of oil applied to the paper had no effect on plant height. Plant height under black plastic mulch was low at the beginning of August but high at the end of August. The low plant height in early August may have been a result of high temperatures from late July through early August (temperatures during those 3 weeks were the highest all summer, up to 100 oF). In contrast, plant height under paper plus soy oil was high at the beginning of August but low at the end of August (Figure 3). Plant height throughout the experiment declined in week two, likely because we followed common basil-growing practices and pinched flowers each week to encourage foliage development. Removing the apical dominance in the plant induced lateral growth that resulted in heavier branches that were initially bent down, thus reducing the plant’s height.

TABLE 1 |

||||||||

| Height

of basil plants grown with 6 mulch treatments. |

||||||||

| Treatment | 5-Aug

|

12-Aug

|

20-Aug

|

26-Aug

|

||||

| Paper | 23.2 |

ab1 |

16.9 |

b |

21.5 |

b |

23.5 |

b |

| Paper + Tung | 19.5 |

ab |

16.9 |

b |

21.3 |

b |

23.6 |

b |

| Paper + Linseed | 14.4 |

b |

17.3 |

b |

21.4 |

b |

23.4 |

b |

| Paper + Soy | 27.3 |

ab |

17.3 |

b |

21.6 |

b |

23.5 |

b |

| Garden Bio-Film | 29.4 |

a |

20.3 |

a |

25 |

a |

27.1 |

ab |

| Black Plastic | 17.4 |

ab |

20 |

a |

23.8 |

ab |

25.9 |

ab |

| p Value | 0.2012 |

0.0392 |

0.0667 |

0.1049 |

||||

| 1

Treatments with different letters (a vs. b) are significant

at p=0.05 level. “P Value” is a way of stating probability

that data represents a true difference as opposed to an artifact

of random sampling. P Values range from zero to one; the smaller

the P Value (closer it is to zero), the more likely the differences

are caused by the treatments. |

||||||||

FIGURE 3 |

|

Height

of basil grown with 6 different mulch treatments. |

|

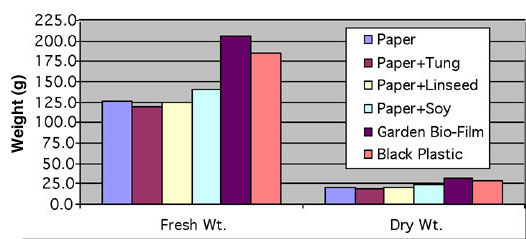

Plant Weights. Basil was harvested on August 25 and fresh and dry weights (g) were measured. Plant fresh weight and dry weight in the Garden Bio-Film mulch treatment tended to be the highest; weights with the black plastic treatment were second highest (Figure 4). However, these differences in fresh weight and dry weight were not significant (Table 2). Basil is a relatively short-season crop and we harvested plants 8 weeks after transplanting. It is possible that a longer-season crop would benefit more from the mulch treatments.

FIGURE 4 |

|

Fresh weight (g) and dry weight of basil grown with 6 mulch treatments.

|

|

TABLE 2 |

||||

| Fresh

weight (g) and dry weight of basil grown with 6 mulch treatments. |

||||

| Treatment | Field

Wt. |

Dry

Wt. |

||

| Paper | 126 |

a1 |

20.8 |

b |

| Paper +Tung | 118.9 |

a |

19.2 |

b |

| Paper + Linseed | 125.2 |

a |

20.5 |

b |

| Paper + Soy | 140.2 |

a |

23.7 |

b |

| Garden Bio-Film | 206.3 |

a |

32.1 |

b |

| Black Plastic | 185.9 |

a |

28.5 |

b |

| p Value | 0.4101 |

0.4173 |

||

| 1Treatments with different letters (a vs. b) are significant at p=0.05 level. “P Value” is a way of stating probability that data represents a true difference as opposed to an artifact of random sampling. P Values range from zero to one; the smaller the P Value (closer it is to zero), the more likely the differences arecaused by the treatments. | ||||

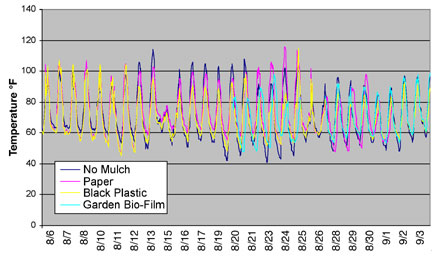

Temperature. Air temperature was measured at the soil surface under paper (with no oil application) and black plastic from August 6 and under Garden Bio-Film from August 20, through September 3. We compared temperatures under the mulches to the temperature at the soil surface without mulch. Temperature fluctuated for each mulch treatment throughout the measurement period so that no treatment consistently produced the highest or lowest temperature (Figure 5). From August 6 through August 12, temperatures were similar under the black plastic and paper mulches as compared to no mulch. From August 13 through August 21, day temperature under no mulch was approximately 5 oF greater than under paper mulch and 10 oF greater than under black plastic mulch. In general, the difference between day temperature and night temperature was greater where there was no mulch than for any of the mulch treatments.

FIGURE 5 |

|

Temperature measured at the soil surface, under paper, black plastic,

Garden Bio-Film and no mulch. |

|

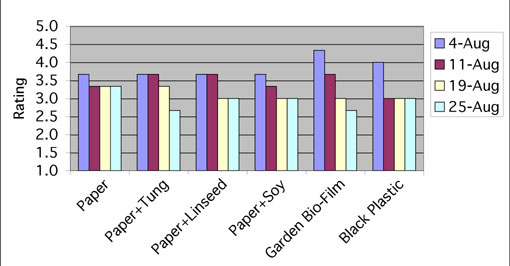

Mulch Quality. We anticipated that the paper and Garden Bio-Film mulches would degrade at the end of the growing season. Indeed, this was the anticipated environmental benefit of the alternative mulches, that they would be plowed into the soil rather than removed and placed in a landfill. Knowing these alternative mulches would degrade, the question was: how well would they hold up during the production season?

We rated mulches on a scale of 1 to 5 where 1 was completely disintegrated and 5 was completely intact. Ratings were based on the mulch’s appearance including rips, holes, thin spots, water damage, mold, and weed growth. Mulches were rated once a week throughout August. In this study there were no significant differences in mulch quality in the field due to the type of mulch. That is, all the mulches maintained their integrity throughout the study and weed control was excellent for all mulch treatments.

Garden Bio-Film and black plastic mulches had the highest ratings on August 4 (4.4 and 4.0, respectively) while the paper mulches were all rated only slightly lower (3.6) (Figure 6). Garden Bio-Film steadily decreased in quality over the 8-week season and by August 25 was rated at 2.6, while black plastic only declined to 3.0. Garden Bio-Film is designed to degrade in one growing season (90 days), thus the small rips and tears that we observed over the course of the study were to be expected. The Garden Bio-Film’s partial degradation during the growing season did not affect plant growth, production, or weed control. Garden Bio-Film degraded completely at plow-down.

The paper mulches, regardless of oil application, all had very similar ratings (3.0–3.6) throughout the experiment. Oil application did not increase the quality of the paper mulch in the field over the course of this study. The 26-lb. paper we used in this study was thick and durable enough so that oil may not have been needed to increase its longevity. Or, we may not have applied sufficient oil to the paper to make a difference. The paper mulch with or without oil maintained its integrity and provided good weed control throughout the study. Three weeks after the September 12 plow-down, remnants of the paper mulch were still apparent in the soil. A potential issue with the paper mulch was that some of it blew away during plowing, which could create an additional concern.

It is important to note that much of the damage to the mulches that we observed was due to human error. Garden Bio-Film and the paper mulches were especially sensitive to any pressure or punctures caused by being walked on or poked with a hoe. Once damaged, the Garden Bio-Film mulch ripped easily. The paper was only easy to damage when it was wet following irrigation. When the paper was dry, it did not puncture or rip easily. The papers sprayed with tung, linseed, and soybean oils had a slight tendency to mold if they were damp on top, which affected the quality and rating of the mulch. Having properly working drip irrigation and hot summer temperatures would eliminate this problem.

FIGURE 6 |

|

Ratings in the field of 6 mulches throughout August. |

|

Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to determine if there are suitable alternatives to plastic mulch with respect to weed control and crop production in the Pacific Northwest. In this study we found that there were no differences in the quality or durability of the alternative mulch treatments or in the quality and yield of the vegetable crop. The oil had no effect on the longevity or qualities of the paper mulch. The paper mulches proved as high in quality as the plastic mulch and Garden Bio-Film. In adjacent observation plots, paper was laid in the field and then oils were applied. There was no difference in quality of the mulch whether oil was applied before or after laying the mulch in the field. In an additional adjacent observation plot, paper with no oil was laid in the field and overhead irrigation was applied throughout the summer. There was no difference in the quality of the mulch whether irrigation was applied through drip or overhead irrigation.

In 2004 we intend to continue investigating alternatives to plastic mulch. We will test different weights of paper and again test Garden Bio-Film mulch. We will also evaluate the response of several types of vegetable crops (warmer temperature vs. cooler temperature) to the different mulches.

Dr. Carol Miles and her co-authors Lydia Garth, Madhu Sonde, and Martin Nicholson conducted their mulch alternatives study at the WSU Vancouver Research and Extension Unit, http://agsyst.wsu.edu. Miles, Sonde, and Nicholson can be reached at (360) 576-6030 or via Miles' email address: milesc@wsu.edu. Lydia Garth is a senior at Columbia River High School in Vancouver. She participated in this study as part of her senior science project.

SOURCES OF MULCH

Paper

Newark Paperboard Products

620 11th Ave, Longview, WA 98632

(360) 423- 3420

Attn: Jim McDaniel, General Manager

Garden

Bio-Film

Biogroup

USA, Inc.

107 Regents PI. Ponte Vedra Beach, FL 32802

(904) 280-5094; Fax: (904) 543-8113; http://www.biogroupusa.com

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION

American Plastics Council. 2003. About plastics. Arlington, VA. http://www.americanplasticscouncil.org/benefits/about_plastics/history.html

American

Plastics Council. 2003. Plastic ranks as one of century’s top news

stories. Stories of the Century, Newseum. Arlington, VA.

http://www.americanplasticscouncil.org/apcorg/newsroom/pressreleases/1999/2-24-top_100.html

Durham, S. 2003. Plastic mulch: harmful or helpful? Agricultural Research, July, p. 14-15.

Futch, S. H. 2003. Weed control in Florida citrus. University of Florida. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/BODY_CH143

Garthe, J. W. 2002. Used agricultural plastic mulch as a supplemental boiler fuel. An Overview of Combustion Test Results for Public Dissemination. Energy Institute, PennState. http://environmentalrisk.cornell.edu/C&ER/PlasticsDisposal/AgPlasticsRecycling/References/Garthe2002b.pdf

Lamont, W. J. 1991. The use of plastic mulches for vegetable production. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center, Kansas State University, Manhattan. http://www.agnet.org/library/article/eb333.html

McGraw, L. 2001. Paper mulch coated with vegetable oil offers biodegradable alternative to plastic. ARS News and Information, USDA. http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/pr/2001/010312.htm

Masiunas, J. B. 2003. Weed competition with vegetables. Weed Management in Fruit and Vegetable Crops. University of Illinois. http://www.nres.uiuc.edu/research/r-masiunas.html

Takakura, T. and W. Fang. 2001. Climate under cover. Kluwer Academic Publishers, p. 1-10. http://ecaaser3.ecaa.ntu.edu.tw/weifang/Bio-ctrl/cuc-chap1.pdf

Go to this issue's Table of Contents

Go to Agrichemical and Environmental News Index

Go to WSPRS (Washington State Pest Management Resource Service) Home Page

Scout Now to Avoid Spruce Aphid Issues Next Summer

Todd Murray, Whatcom County IPM Project Manager, WSU

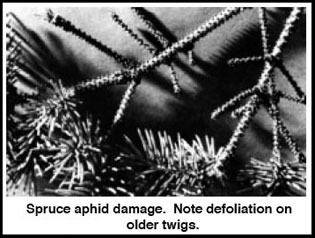

Early this past summer, Agrichemical and Environmental News ran a short article about spruce aphids (“Sprucing Up Your IPM Skills," AENews Issue No. 206, June 2003, http://aenews.wsu.edu/June03AENews/June03AENews.htm#SpruceAphid). While damage from spruce aphid was very visible throughout western Washington last May and June, we pointed out that the time to control this pest was not summer, but fall and winter. The colder months are not when we normally think about pest control, but pests like spruce aphids are active and damaging trees at this time.

Spruce aphid is a pest on many kinds of spruce, particularly Sitka spruce. As with so many insect pests, monitoring its population is key to successfully managing it. Spruce aphids begin to become active as the weather cools and the fall season begins. Beginning in October and November, aphids start to resume their busy little lives, which consist primarily of the spellbinding activities of sucking plant juice, squirting honeydew, and making babies. This is the time to turn a watchful eye on the activities of these aphids, especially if you experienced an infestation this past year.

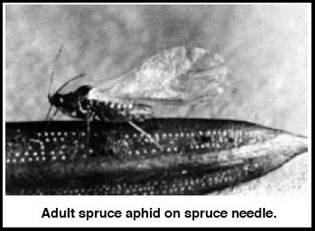

Spruce aphids (Elatobium abietinum) are winged or wingless, 1 to 1.5 mm long (small), olive green to very dark in color, and pear-shaped. The head end can be yellowish green with reddish eyes. They have piercing/sucking mouthparts that are, as with all aphids, directed straight downward. The spruce aphid’s legs are long (well, long for a 1-mm insect…) and slender.

|

|

The best and easiest way to monitor your spruce aphid population is to use a beating tray. Mine is a white canvas square supported by PVC tubes, but a stiff piece of white card stock works just fine. Hold the card or tray underneath the tips of branches (new-growth areas) and bump the card or tray against them or brush two branches together to dislodge any aphids. Do this in several locations around the tree to jar any aphids off the spruce needles and onto your card.

If you find any aphids at all (and look closely, because they are small!), even one or two per tap, you may have a problem. Make a note of the number you find, then repeat the tapping process weekly. Be sure to use the same monitoring techniques each time so you can compare each week's numbers. If you see a sudden increase, consider treatment. Low temperatures can knock the population down, so you may want to continue monitoring and wait it out if a freeze is in the immediate forecast.

The first line of defense is directing a water spray at the aphids. Use a stiff, forceful jet of water to knock the aphids to the ground. Repeat this process every few days until you see a decline in aphid numbers.

If despite all your efforts, the population rapidly increases toward the end of winter, consider using an insecticide at that time. Don't wait until late spring when the damage is intolerable but the pest population has already fallen to low levels. Point your Internet browser to WSU’s Hortsense homeowner gardening site (http://pep.wsu.edu/hortsense/), refer to the Pacific Northwest Insect Management Handbook (http://pnwpest.org/pnw/insects), or read Dr. Art Antonelli’s Spruce Aphid extension bulletin (http://cru.cahe.wsu.edu/CEPublications/eb1053/EB1053.pdf). Whenever you use a pesticide, be sure to read the label and follow directions.

Todd Murray (tamurray@coopext.cahe.wsu.edu) is the manager of Whatcom County’s Integrated Pest Management Project. The Whatcom County Extension Office can be reached by telephone at (360) 676-6736. For the Cooperative Extension office in your Washington State county, go to Internet URL http://ext.wsu.edu/locations/.

Go to this issue's Table of Contents

Go to Agrichemical and Environmental News Index

Go to WSPRS (Washington State Pest Management Resource Service) Home Page

Items in this section often appear in the words of the sponsoring organization or original news release. AENews editorial staff is not responsible for the accuracy of the content.

OktoberPest: Every Thursday in October

Pest Management Workshops for Greenhouse and Nursery Growers

The third annual OktoberPest Pest Management Seminar Series is rearing its head again.The agenda for OktoberPest is available at the Internet URL below. Once again Oregon State University will offer workshops focused on a variety of pest-related topics. They've even thrown in a workshop on a non-pest topic for the positive thinkers out there. Workshops are held at OSU’s North Willamette Research and Extension Center.

http://oregonstate.edu/Dept/nurspest/OktoberPestagenda03.htm

The 4th Annual National Pesticide Stewardship Alliance (NPSA) Conference will be held October 19 through 22, 2003, in Tucson, Arizona. This year's theme is Stewardship Issues: Discussions for a Global Community. Focus topics will include the future of state pesticide disposal programs, residential pesticide stewardship, and label language pertaining to container disposal.For more information on the conference and the NPSA organization, visit their Website:

November 7-9, 2003, the Tilth Producers, a chapter of the Washington Tilth Association, presents “Sound Farming: Listening to the Environment.” The conference runs Friday 5:00pm through Sunday 3:00pm. A special one-day symposium on "Organic Farming Principles and Practices" with Amigo Cantisano will also be presented on Friday, November 7, from 10:00am to 4:00pm. The conference will be held at the Best Western Lakeway Inn & Conference Center in Bellingham. For more information,

Wine Grape Growers Conference, Feb. 2004

The Washington Association of Wine Grape Growers (WAWGG) will hold its annual conference Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, February 4 through 6, at the Yakima Convention Center. More information about this conference and other wine grape grower events can be found at

http://www.wawgg.org

The conference includes a trade show, and sign-ups for booths have begun. Visit the Website for details.

The 2004 National Monitoring Conference, "Building and Sustaining Successful Monitoring Programs," is slated for May 17-20 in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Join us as we explore and share the experiences, expertise, lessons learned, innovations, and strategies that strengthen and sustain both the technical and institutional elements of our monitoring programs.

The Chattanooga meeting will be the fourth National Monitoring Conference hosted by the National Water Quality Monitoring Council (NWQMC). Like its predecessors, the 2004 Conference will provide an outstanding opportunity to participate in technical programs and trainings, share successes, discuss issues, and network with our colleagues in the water monitoring community. The conference agenda will include plenary sessions, workshops, paper presentations, posters, exhibits, facilitated discussions, field trips, and informal networking opportunities.

NWQMC and the Framework for Monitoring the Council, chartered in 1997, promotes partnerships to foster collaboration, advance the science, and improve management within all elements of the water monitoring community, as well as to heighten public awareness, public involvement, and stewardship of our water resources. The Council has developed a monitoring and assessment framework that describes a sequence of steps that produce and convey the information necessary to understand our water resources. This conference will weave together several themes related to the framework including changing expectations of monitoring, new and emerging technologies, collaborative efforts, data and information comparability, and sharing results and successes.

A call for abstracts will be issued within the next few weeks. If you have additional questions about the conference or would liked to be placed on a mailing list for information as it becomes available, contact the 2004 Monitoring Conference Coordinator at NWQMC2004@tetratech-ffx.com or 410-356-8993. For more information about the Council, visit

Go to this issue's Table of Contents

Go to Agrichemical and Environmental News Index

Go to WSPRS (Washington State Pest Management Resource Service) Home Page